Gaussian Splats for Dummies

A Studio JDB guide to reality-capture visualisation (without the techno-mysticism)

Most clients don’t struggle to approve design because they “don’t like design.”

They struggle because they can’t see it.

Not in the abstract. Not in plan view. Not in polite little elevations.

They need to feel scale, context, and consequence.

That’s what project visualising is really for: reducing uncertainty.

And in the last couple of years, a new tool has quietly entered the room and started rearranging the furniture: Gaussian splatting.

It’s not magic. But it can feel like it when you see your site captured as a navigable, photoreal environment—without the heavy “traditional 3D model everything” burden. Let’s break it down in plain language.

The problem: design doesn’t live in a vacuum

A design model can be perfect and still be hard to evaluate because:

the site is missing

the context feels generic

scale cues aren’t believable

the lighting doesn’t match reality

stakeholders can’t “locate themselves” in the proposal

So we spend a lot of our workflow energy on one thing: making the context trustworthy.

Studio JDB’s baseline workflow (the “good enough” stack)

We usually begin with SketchUp because it’s fast, intuitive, and supports the way designers actually think: iteratively, visually, and spatially.

From there, we can get strong results with:

sun/shadow studies (time-of-day truth)

ambient occlusion (depth readability)

material tuning (reflection + roughness cues)

simplified surrounding modelling (sense of place)

And when we can, we layer real-world context:

site photos as backplates

panoramas for quick immersion

360 HDRI environments for believable light and reflections

This is already powerful. But it still depends on a lot of “creative reconstruction.”

Reality capture changes that.

Reality capture, explained like you’re busy

Reality capture is when you measure and record the real site using photos or scanning, so you can bring it into your design workflow.

There are a few major “outputs” you’ll hear about:

Photogrammetry

Lots of overlapping photos → software reconstructs 3D geometry.

Great for objects, facades, terrain, and “scan-to-model” work.

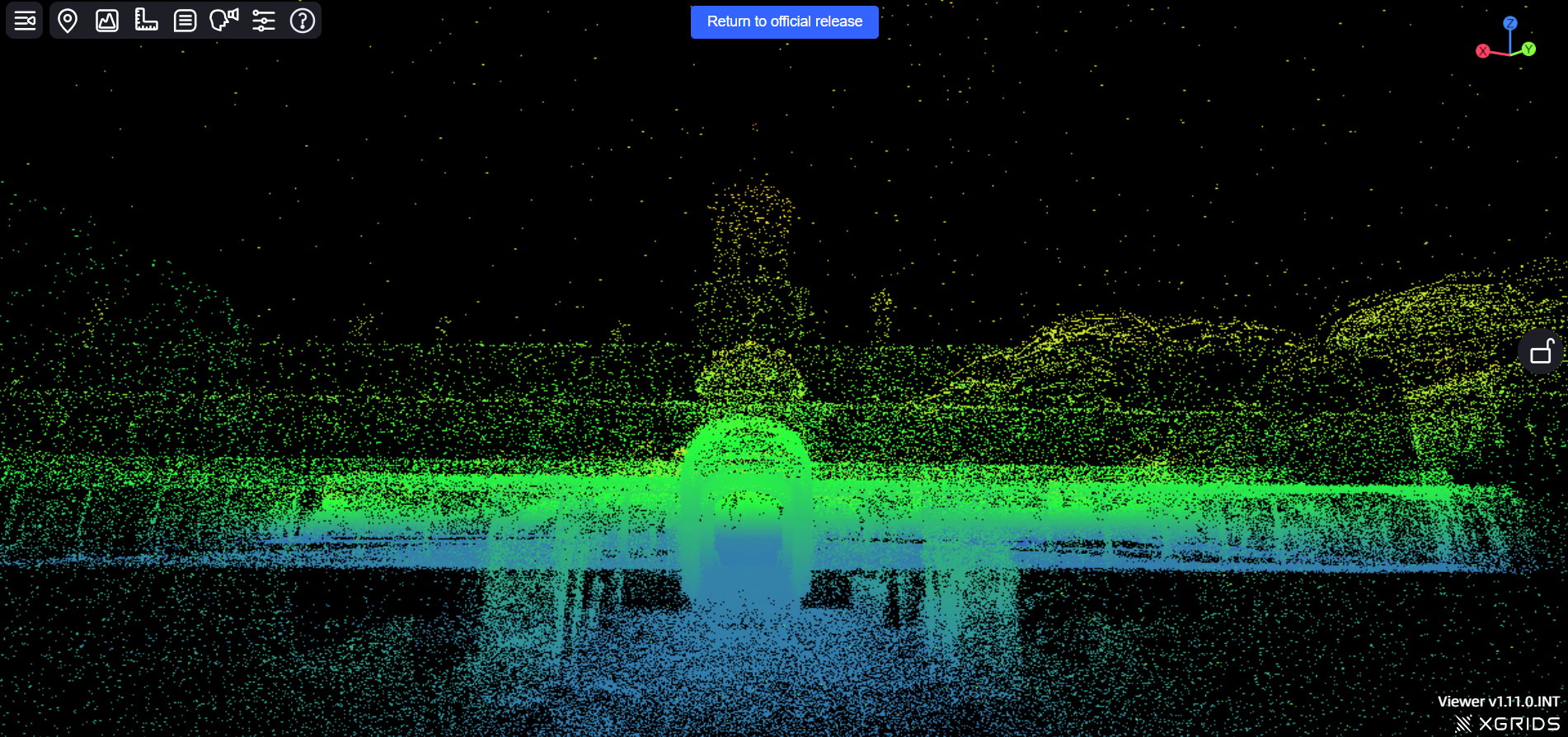

Point clouds

Millions of measured points in 3D space (often from LiDAR).

Excellent for accuracy: levels, openings, dimensions, setout.

Gaussian splats

A capture-based representation that looks shockingly real when you navigate it.

Often faster to create and more visually convincing than a traditional mesh model — especially for complex, messy environments (vegetation, rubble, irregular textures, cluttered interiors).

The headline:

Point clouds help you measure.

Splats help you feel.

So what is Gaussian splatting, really?

Imagine you walked through site and sprinkled the space with tiny “smart paint droplets” that remember:

colour

brightness

softness

how they should look from different angles

A Gaussian splat scene is basically a huge collection of those droplets.

When you move through it, the system renders them in a way that feels continuous—so instead of “points,” you experience a space.

It’s not a perfect substitute for a clean 3D model.

It’s a different kind of truth: experiential truth.

Where splats shine (and where they don’t)

Splats are excellent for:

immersive walkthroughs of real environments

quick capture of complex spaces

stakeholder presentations where context matters

VR / web-based navigation experiences

keeping remote teams aligned on “what the site is actually like”

Splats are not ideal for:

crisp, editable construction geometry

clean linework outputs

situations where you need perfect CAD-level surfaces

heavy downstream editing (you don’t “model” a splat like you model geometry)

A good rule:

If the goal is designing → you still need clean 3D geometry.

If the goal is believing → splats are a cheat code.

How we use them: two “site layers” inside the workflow

When we’re staging designs into real contexts, we often combine:

1) Point cloud layer (dimensionally honest)

Used for:

setout and alignment

checking clearances and heights

verifying relationships between existing elements

giving the model an accurate “skeleton”

2) Gaussian splat layer (photoreal immersion)

Used for:

realistic walkarounds

stakeholder viewing

team immersion (especially if not everyone visited site)

making the site “present” while discussing options

Together, they cover both sides of the problem:

precision + presence

measurement + meaning

Visualising tools: choosing your output lane

Once you’ve got:

a SketchUp concept model

plus site capture (point cloud / splat / HDRI)

…you choose your output based on what decision needs to happen next.

V-Ray (when you want controlled, cinematic clarity)

strong for hero stills

strong for lighting craft

strong for refined material realism

great when the design needs to “land” emotionally

D5 Render (when you want speed + walkthrough energy)

fast iteration

real-time-ish feedback

great for stakeholder walkthroughs

ideal for “let’s test three options quickly”

Think of it like:

V-Ray = precision storytelling

D5 = momentum + interaction

Both can play beautifully with reality-captured context, depending on pipeline and presentation approach.

The real deliverable: confidence

Clients don’t buy files.

They buy certainty.

So our presentations focus on:

what’s fixed vs flexible

what the design changes in the real world

key viewpoints (human height, approach, arrival, threshold)

the context cues that make scale believable

the walkthrough moments where questions naturally appear

The job isn’t “wow.”

It’s making the right decision easier.

FAQ: Gaussian Splats (for normal humans)

1) Is Gaussian splatting the same as photogrammetry?

No. They’re related but different outputs.

Photogrammetry typically reconstructs geometry (meshes/textures).

Gaussian splats reconstruct appearance and viewpoint realism in a splat-based representation.

2) Is a splat “accurate”?

Visually, yes. Dimensionally, not always in the way a point cloud is.

Use splats for immersion and context; use point clouds for measurement.

3) Can I edit a Gaussian splat like a 3D model?

Not in the same way. You generally don’t “push/pull” a splat.

It’s best treated as a reality backdrop or navigable reference environment.

4) Do I still need SketchUp (or Revit, etc.)?

Yes. Splats are not a replacement for design modelling.

They’re a site truth layer that makes design decisions more grounded.

5) What’s the minimum gear to start?

You can start with a phone-based capture workflow, but quality varies.

If you’re doing this often, a 360 camera and/or LiDAR-capable device can improve consistency.

6) Where does a 360 camera fit in?

A 360 camera is a strong “mid-step”:

fast site context

HDRI lighting/reflections

great for backplates and environment realism

Splats are the step beyond: navigable, immersive context.

7) When is it worth paying for splats / scanning?

When any of these are true:

the site is complex or hard to model

you want fewer site revisits

stakeholders struggle to read drawings

decisions depend heavily on context (heritage, tight urban sites, interiors, renovations)

remote collaboration is a constant

8) What’s the best client-facing output?

Usually:

a short guided walkthrough (web-hosted) +

5–10 curated stills of key moments +

1 “truth shot” showing context capture alongside the design intent

The best output is the one that answers the client’s next question before they ask it.

9) What are the common pitfalls?

treating splats as “final model” rather than context layer

over-promising accuracy without a point cloud

capturing poorly (motion blur, low overlap, inconsistent lighting)

using tech to impress instead of clarify

10) What’s the simplest way to explain splats to a client?

We use reality capture when the cost of misunderstanding is higher than the cost of capturing.

Because nothing burns budget faster than decisions made in a fog.